Buying the Big 5

An innovative retailer that has risen to dominate the sector and is unmatched in scale and logistics. A company that has revolutionized the way we communicate. A consumer electronics powerhouse that has continually reinvented itself to stay on the cutting edge. Who wouldn’t want to invest?

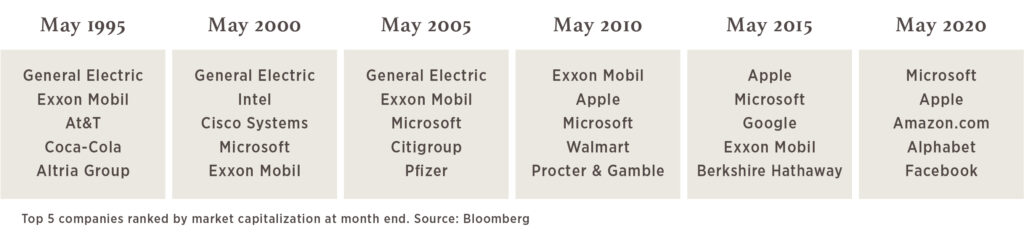

We are not referring to the current investment darlings Amazon, Facebook and Apple, but instead three of the largest stocks in the S&P 500 in 2008 (Walmart, AT&T, and GE). There is comfort investing in the largest, most successful companies. They are household names, the market has recognized and rewarded their dominance, and winners take all. Right? Not so fast.

It may sound appealing to buy the top 5 stocks by market cap but historically this has not been a strategy that outperforms. The biggest companies by stock market valuation rarely keep their top spot over the long term. In 2008 the five largest stocks were the three mentioned above as well as Microsoft and Exxon Mobil. A portfolio consisting solely of those 5 stocks lagged the S&P 500 by 9.4% over the three years from May 31, 2008, returning negative 6.7% in total compared to positive 2.7% for the index.

Exxon and GE are both worth significantly less today than they were 12 years ago. AT&T is only worth slightly less as a company, but against the backdrop of a rising market. Walmart has risen in value, but has not kept up with the broad market. Only Microsoft is in the top 5 list again, and that comes after several periods of underperformance in the interim. This should come as no surprise to anyone who remembers the Windows Phone.

The previous example is not an isolated one.

We tested a strategy of consistently buying the largest 5 stocks by market cap with data going back to 1992, giving the hypothetical investor the benefit of monthly rebalancing to keep the lineup of top names fresh. The result was a fairly consistent pattern of lagging the market with no commensurate reduction in volatility. The portfolio compounded at 0.36% less per year than the market, returning 9.14% annualized over 28 years compared to 9.50% for the S&P.

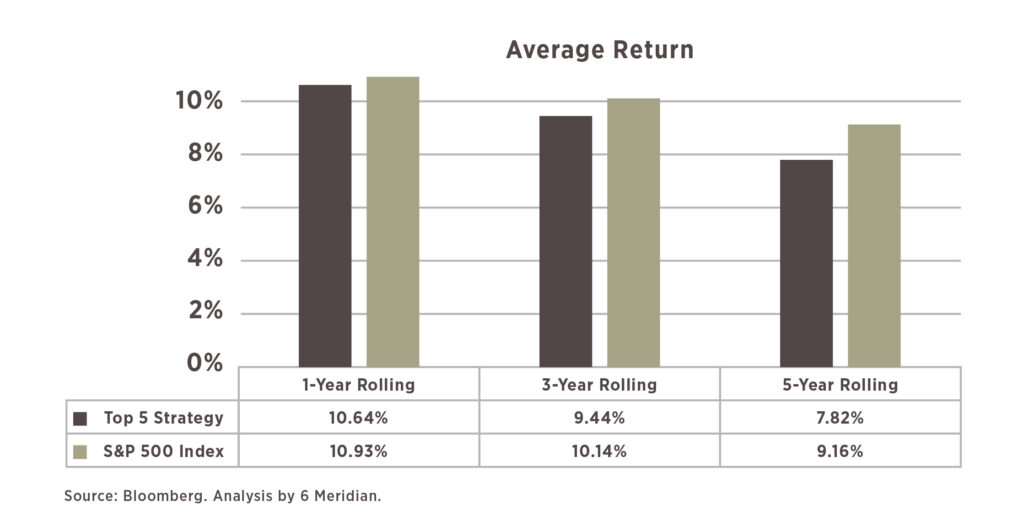

Breaking down this performance difference into rolling time periods, we find that average return over a 1-year time horizon has been comparable between the largest stocks (10.64%) and the index (10.93%), with the portfolio of the largest stocks outperforming about half of the time. However, as seen in the chart on the next page, the top 5 portfolio has lagged by more on average as the time frame measured gets longer. In 3-year time frames, the top 5 portfolio lagged by 0.70% per year on average and only beat the index 38% of the time. Looking on a 5-year basis, the underperformance grew to 1.34% a year with only 29% of periods returning at least as much as the index.

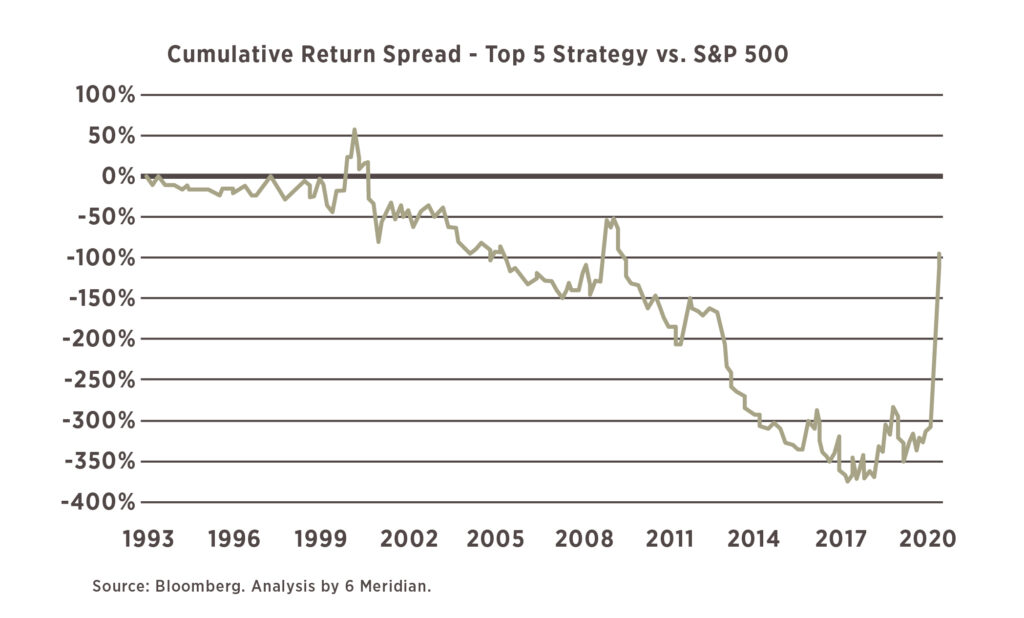

The consistent pattern of underperformance from the largest companies looks even more remarkable when we consider the effect of the past few months. The period from September 2019 through April 2020 was both the largest and the longest sustained runup in the relative return of the top 5 stocks versus the S&P. As recently as a year ago the top 5 strategy was trailing the index by over 300% in cumulative terms. The gap has since narrowed to 100%.

The consistent pattern of underperformance from the largest companies looks even more remarkable when we consider the effect of the past few months. The period from September 2019 through April 2020 was both the largest and the longest sustained runup in the relative return of the top 5 stocks versus the S&P. As recently as a year ago the top 5 strategy was trailing the index by over 300% in cumulative terms. The gap has since narrowed to 100%.

For the past 8 months, it would have been a market beating strategy to only own a portfolio of Apple, Microsoft, Facebook, Alphabet (Google), and Amazon, so much so that almost any other strategy has looked like a costly mistake in comparison. Is it possible that we are in a new regime in which the historical pattern of the largest stocks losing their momentum no longer matters? It is certainly not impossible, but we believe the strategy of holding the top 5 names will continue to be a bad one for three reasons – valuation, concentration, and disruption.

Valuation

Increases or decreases in a company’s market value can be broken down into two effects – the change in fundamentals, such as earnings, and the change in valuation, or the multiple investors are willing to pay for those earnings. For example, a stock with a share price of $10 and $1 of earnings has a P/E multiple of 10x. If the earnings grow to $1.25 and the P/E multiple that investors pay increases to 12x then the stock price would move up to $15. A 25% increase in earnings and a 20% increase in the P/E multiple results in a 50% increase in the share price.

For a top stock in the index to remain at the top, one of two things must happen. The company must continue growing at a higher rate than all other companies in aggregate, or investors must be willing to pay an increasing P/E multiple for those earnings relative to what they are willing to pay for the earnings of all the other companies in the index.

In recent months, the second of those effects has been in full force. The P/E ratio for the S&P 500 index rose from 19.8x on September 30, 2019 to 21.2x at the end of May 2020 for a change of 7%. Over the same eight months, the P/E ratio of the top 5 stocks rose from 34.0x to 47.8x. During this time, the S&P 500 price increased by 2.2% and the top 5 strategy increased by 31%.

A higher valuation multiple generally means that investors are putting more weight on future growth. The problem with extrapolating index-beating growth far into the future for already successful companies is that individual companies cannot outgrow the economy forever. If companies that are already the largest in the world continue to grow at a meaningful rate above the growth of the economy then they would become disproportionately large pieces of both the index and the economy, which brings up our next concern: concentration.

Concentration

To put it simply, a company cannot grow faster than the economy forever – it would become larger than the entire economy. For a market-based capitalist system to function, a level of competition between firms is necessary. Regulators and consumers understandably become wary of firms that amass too much scale. It may not be a coincidence that concerns over inequality are on the rise as a few companies concentrate an increasing share of economic weight.

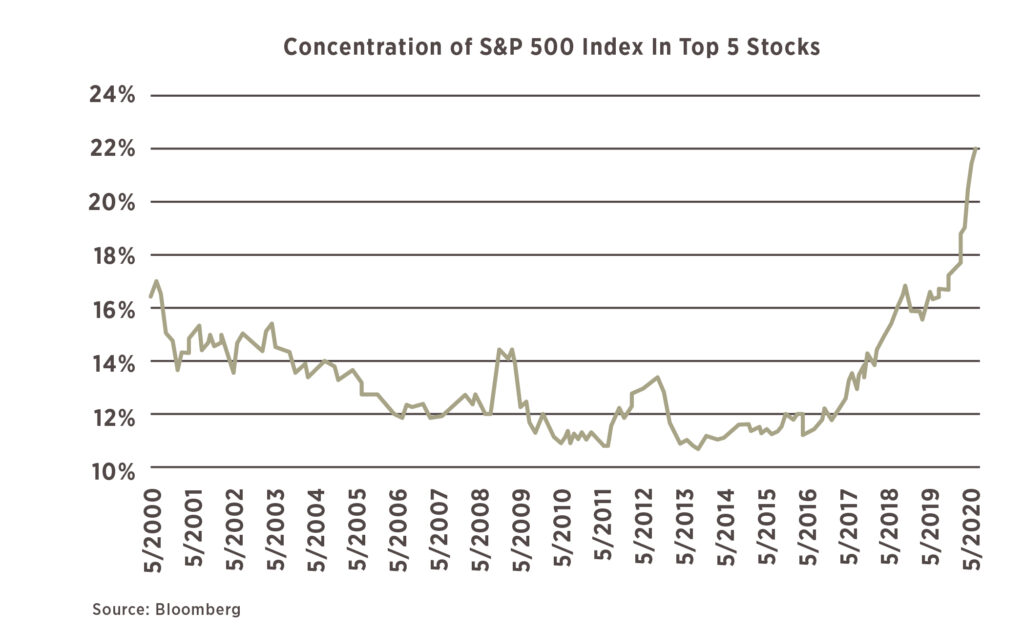

Just as an economy too heavily concentrated in a few companies poses societal risk, having a portfolio or even an index concentrated in a few companies increases investment risk. The top 5 stocks currently represent over 20% of the S&P 500 index, comparing to an average of 13% over the past 20 years.

For the past 8 months, it would have been a market beating strategy to only own a portfolio of Apple, Microsoft, Facebook, Alphabet (Google), and Amazon, so much so that almost any other strategy has looked like a costly mistake in comparison. Is it possible that we are in a new regime in which the historical pattern of the largest stocks losing their momentum no longer matters? It is certainly not impossible, but we believe the strategy of holding the top 5 names will continue to be a bad one for three reasons – valuation, concentration, and disruption.

As this concentration increases, index investors and benchmark-aware asset managers must increase their holdings of the top names just to keep up. This results in crowded positioning which can increase volatility. To make matters worse, all five of the top companies are currently focused on a few overlapping pools of revenue – namely ad-based media, cloud computing, and mobile device sales & service. This could open the door to our third concern: disruption.

Disruption

One argument we often hear for why this time is different is that the current occupants of the top 5 spots have disrupted and innovated their way to the top, and innovation is incredibly and intangibly valuable. That may be true, but it was also true for AT&T, IBM, and the vast majority of top 5 stocks throughout history. When Bank of America and Citi were two of the top 5 in 2006, it was arguably because they had disrupted the way that mortgage securitizations were sold – a gentle reminder that not all disruption has good outcomes! The common thread is that it is difficult for any one company to remain world-beating and also fast-growing over long periods of time. An individual company could have its business model disrupted by a challenger, as in the case of Walmart and Amazon, or an entire industry could be shaken up as we saw with the banks and with Exxon. In any case, size and scale are no guarantee that a company can maintain its competitive position over the very long term.

This is not meant to be a recommendation for or against any of the specific companies listed above. We are not in any way rooting for the current top five companies to fail. We are simply pointing out that buying stocks at the top of the index based on recent success and current market dominance has been a poor strategy in the past. We believe it is likely to be a poor strategy going forward as well.

Contributors

Andrew Mies, CFA® Chief Investment Officer

Will Horner, CFA® Investment Management Associate