You’ve spent the last several decades responsibly saving as much as possible in a tax-efficient manner, including by contributing to your tax-deferred accounts. Now it’s finally time to enjoy your retirement, but a new, possibly daunting era of managing cash flow and taxes awaits.

An important step in preparing for this new era is understanding required minimum distributions (RMDs), the IRS-mandated withdrawals you will need to take from your tax-deferred accounts. Knowing ahead of time how they are calculated, roughly how much of your overall spending they might cover, and their tax consequences can pay off by helping you make decisions about how to optimize them.

To help, here is an overview of RMDs and examples of strategies you may want to consider when you begin taking them.

What are RMDs?

Taxes on assets held in many retirement accounts, such as most IRAs and 401(k)s, are deferred. Contributions to the accounts are made on a pre-tax basis, and the investments within them are allowed to grow tax-free until they’re withdrawn, at which point they become subject to income taxes.

To ensure that retirement accounts are not merely vehicles used to transfer assets to heirs, thereby avoiding income and estate taxes, IRS rules require that participants withdraw specified minimum amounts annually. In this way, the government “harvests” taxes that participants avoided through pre-tax contributions and tax-deferred growth during the accumulation phase of their retirement savings.

Generally, the following tax-deferred and employer-sponsored accounts are subject to RMDs:1

• TRADITIONAL IRAS

• SEP IRAS

• SIMPLE IRAS

• 401(K) PLANS

• 403(B) PLANS

• 457(B) PLANS

• PROFIT-SHARING PLANS

• OTHER DEFINED-CONTRIBUTION PLANS

• ROTH IRA BENEFICIARIES

Note that RMDs do not apply to Roth IRAs. As such, in some situations, converting your existing account into a Roth IRA may enable you to reduce your tax liabilities while in retirement.

When Must I Begin Taking RMDs?

Retirement account owners are required to begin taking RMDs by April 1 of the year following the year in which they reach age 72 (73 if you reach age 72 after Dec. 31, 2022.) This is the latest date on which the owner can take the first RMD from the account without a penalty tax.

For example, if you turn 73 on November 30, 2024, the latest date to take your 2025 distribution is April 1, 2026. But by waiting until this date, you would need to take two withdrawals in 2026 — the 2025 distribution by April 1 and the 2026 distribution by December 31. Depending on your situation, it may be better from a tax perspective to take the 2025 distribution by December 31, 2025. Then, you would need to take future RMDs by December 31 of each new tax year to avoid an excise tax.2

However, you may delay taking withdrawals until April 1 of the year following the year you retire (if later than the year you reach age 73) under two conditions:

- The distribution is from a qualified retirement plan. IRA distributions do not qualify (including SEP IRAs and SIMPLE IRAs)

- You own 5% or less of the company that maintains the plan

How are RMDs Calculated?

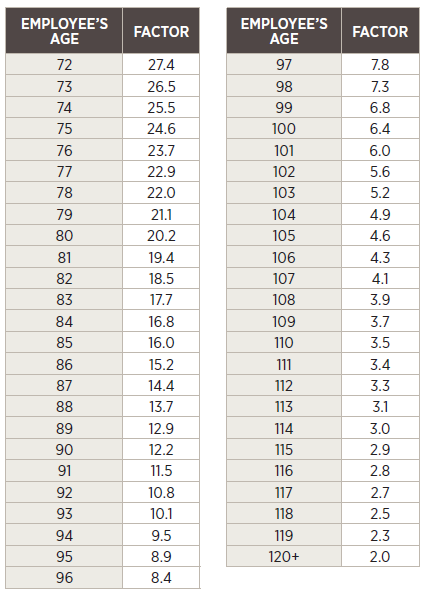

The Uniform Lifetime Table from the IRS is used to calculate required minimum distributions from your applicable retirement accounts — unless your spouse is the sole beneficiary for your retirement account and is more than 10 years younger than you.

To determine the required minimum distribution for any distribution calendar year (a calendar year for which a minimum distribution is required), identify (1) your account balance on the last valuation date of the preceding year, (2) your age on your birthday in the distribution calendar year, and (3) the divisor that corresponds to that age in the Uniform Lifetime Table.

Please note that with recent revisions to the IRS’ life expectancy tables, RMD payouts to beneficiaries if the account owner dies before January 1, 2022 may be determined on the new tables in certain situations. Please consult your advisors for more information.

The following example illustrates an RMD calculation:

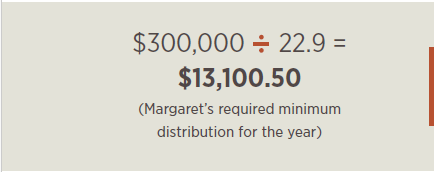

Mary is 77 years old and owns an individual retirement account that has a year-end market value of $300,000.

The distribution period that corresponds to Mary’s age is 22.9, so her RMD calculation would look like this:

Keep in mind that while you must make a minimum withdrawal, there’s nothing stopping you from withdrawing more than that amount — although you should consult with your financial advisor before doing so. Also, note that if you own more than one retirement account, you’re responsible for making RMDs from each one, and these amounts must be calculated separately.

What’s the Penalty for Missing an RMD?

Failing to comply with the RMD rules results in a severe penalty — a 50% excise tax (SECURE 2.0 Act drops the excise tax rate to 25%; possibly 10% if the RMD is corrected within two years) on the difference between the amount that should have been distributed (the RMD) and the amount distributed. For example, if you should have taken a $50,000 RMD but took only a $30,000 distribution, the penalty would be $10,000 (50% of the $20,000 you failed to take). This penalty tax is in addition to any ordinary income tax due on the distribution.

What RMD-Related Considerations Should I Discuss with My Advisor Ahead of Time?

While RMDs are just that — required — there are certain financial planning strategies that may help you take advantage of them more efficiently. Below are a few examples:

- Process: First and foremost, make sure you have a plan in place for taking the withdrawals. Talk to your advisors about their approach — how and when they might remind you, how they collaborate with one another (i.e., your accountant with your financial advisor), etc.

- Income-Liability Matching: Try to plan so that you can time your RMD around large, expected expenses and thereby avoid unnecessarily needing to sell assets from one of your other accounts to fund them.

- In-Kind Transfers: Your RMD does not need to be in the form of cash. Instead, you can transfer a certain number of shares of a mutual fund or stock, for example, if the value of the shares on the day of distribution is at least equal to your RMD. This strategy can particularly make sense for assets that you believe are at temporarily depressed values. If so, when you make the withdrawal, the assets would be taxed at ordinary income rates, but at lower valuations. And thereafter, you would owe taxes on appreciation only when you sell them, and at a more favorable capital gains tax rate.

- Donor-Advised Funds: A donor advised fund (DAF) provides individual donors with a flexible, tax- efficient vehicle to make donations to 501(c)(3) tax-exempt charities. The assets in your fund can grow tax free, generating more dollars to support the designated charities, all while providing you with the maximum tax deduction allowed by law. This distribution counts toward your RMD, but is not excluded from your taxable income.

- Qualified Charitable Distributions: If you are 70 1/2 or older, you can make a qualified charitable distribution (QCD) from your IRA of up to $105,000 to a qualified charity.3 This distribution counts toward your RMD and is excluded from your taxable income, even if it exceeds your RMD.

- Withdrawal Sequencing: While conventional wisdom in retirement planning suggests you should withdraw and deplete taxable accounts before withdrawing from retirement accounts, to the extent possible (RMDs are unavoidable), this strategy doesn’t always result in optimal results once you account for taxes. To decide how to sequence your withdrawals, talk to your advisor, who can help align your strategy with your anticipated income, tax brackets, and unrealized gains and losses across your investment accounts.

The above techniques are simply examples of how advanced planning with your advisor can lead to more efficient use of your RMDs. For more possibilities, and for help more broadly fine-tuning your retirement plan, please reach out to one of our advisors.

1 – Internal Revenue Service, “Retirement Topics — Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs),” https://www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/plan-participant-employee/retire-ment-topics-required-minimum-distributions-rmds. Accessed May 20, 2022.

2 – congress.gov,H.R.2617-ConsolidatedAppropriationsAct, 2023 (https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/2617/text)

3 – https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/401k-limit-increases-to-23000-for-2024-ira-limit-rises-to-7000